Dr. Kimberly Lanni: Ethics Concerns Plague Kaiser Psychologist's Autism Research

Lanni's 2011 PhD dissertation evokes legacy of abuse

Me reading this article on Youtube

Thanks to autistic psychologist Dr. Henny Kupferstein for her guidance and expertise, Tanya Melnyczuk, Collaboration Director for the Autistic Strategies Network in Cape Town, South Africa, for the very helpful feedback and suggestions, and to neuroscientist Dr. David Putrino of Mount Sinai Hospital, New York for his response to this blog.

FULL DISCLOSURE:

The following blog was conceived in an effort to start an open-ended conversation about ethics in autism research. I am not a scientist, but a former music journalist, editor, horror fiction author and English composition instructor forced into retirement in middle age by a severe neurological disorder, diagnosed as acquired apraxia as a result of parietal lobe damage of unknown etiology. I also have the specific learning disability of dyscalculia and identify as neurodivergent.

In the interests of full disclosure, I saw Dr. Kimberly Lanni as a Kaiser Permanente patient for neuropsychological testing/evaluation of cognitive deficits in 2019.

This blog is deliberately designed to be an ongoing collaborative effort rather than a finished product. Although I am open to all voices, I am particularly interested in the feedback and opinions of autistic researchers. All responses will be appended to the end of this blog and/or incorporated into the body of the text, as appropriate. If after you read this blog you feel it is appropriate, Dr. Kimberly Lanni’s email is kimberly.e.lanni@kp.org. I’m not doxxing here because this is publicly available information with a simple Google search request. Up till now she’s been living easy with her 100k annual salary. Maybe she needs to hear from autistic people and their caretakers about what her practices.

TRIGGER WARNING: CONTAINS GRAPHIC DESCRIPTIONS AND ILLUSTRATIONS OF ABUSE OF AUTISTIC CHILDREN

Left: Kaiser Permanente neuropsychologist Kimberly Lanni, a self-identified “scientist-practitioner.” Right: Lanni’s mentor Vanderbilt University/UC Davis M.I.N.D. Institute autism researcher, psychologist Blythe Corbett

Autism research by Dr. Lanni raised methodological and ethical issues

According to her UC Davis curriculum vitae, Dr. Kimberly Lanni participated in the Autism Research Training Program from May 2008 – September 2008 at the University of California, Davis, M.I.N.D. Institute, through which she became associated with Vanderbilt University psychiatry professor Blythe Corbett.

In August 2011, Lanni’s paper “Verbal Ability and Social Stress in Children with Autism and Typical Development” was published as her dissertation towards a PhD in Psychology at Washington State University. Blythe Corbett acted as her fourth external thesis advisor.

According to Lanni, “the purpose of the…study was to investigate the neuroendocrine (cortisol) and psychological (anxiety) response to performance of the TSST-C [Trier Social Stress Test for Children] in children with autism…and to determine the association between physiological stress and anxiety.” Lanni stated that studying the stress response as “one precipitant of anxiety” was a “way to broaden our understanding of anxiety in autism without exclusive reliance on

self-report and parent-report measures.”

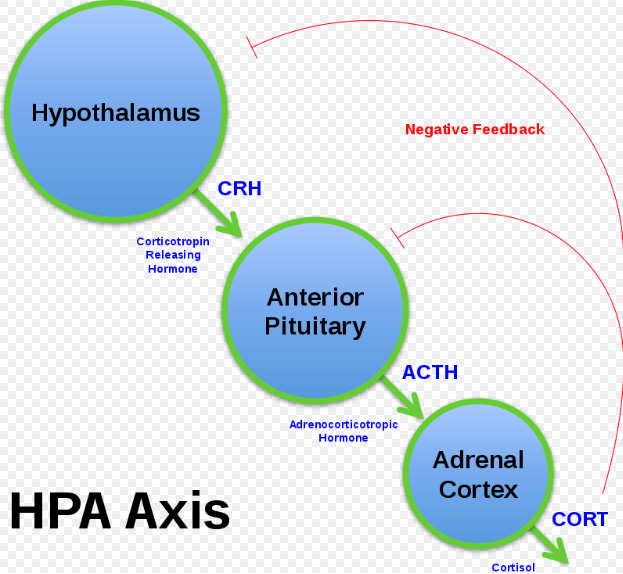

Cortisol is is a product of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical [HPA axis] stress response. “Activation of the HPA axis causes secretion of glucocorticoids, which act on multiple organ systems to redirect energy resources to meet real or anticipated demands” (James P. Herman et al., “Regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical stress response,” 2016, Comprehensive Physiology).

So what does all this jargon mean? Basically, we’re talking about fight or flight.

Let’s break it down.

When the brain perceives a threat, the hypothalamus triggers the HPA axis, which involves a cascade of hormonal responses. This triggers the release of cortisol from the adrenal glands, which helps prepare the body for the fight or flight response. Cortisol increases blood sugar levels, enhances cardiovascular function, suppresses immune responses, and heightens alertness —all of which aid in preparing the body to either confront the threat (fight) or flee from it (flight).

So how does all this apply to the Lanni study? Here’s how: Following the tracks that Corbett had laid out for her, Lanni attempted to induce a fight or flight response in autistic children, under laboratory conditions, who had no ability to control the outcome or opt out (other possibilities include their freezing, withdrawing or engaging in repetitive behaviors due to the stress).

HPA Axis (wikipedia)

This first iteration of Lanni’s social stress study was published as a conference paper in 2009. This was the basis of her PhD dissertation in 2011. A later version of the study was published online in 2011 and published in final form in Autism magazine in 2012. Lanni added the Delis Kaplan Executive Function System (DKEFFS) Verbal Fluency Test and NEPSY Narrative Memory test to the TTST-C as “predictor variables.”

In the epublished 2011 iteration of the study, Lanni et al. concluded that “despite the utility of the TSST-C as a reliable and valid social stress protocol in typically developing children, the current findings…suggest that it may not be a relevant paradigm to elicit social stress in children with autism.”

Lanni stated that “research on social cognition in autism has documented abnormalities in social perception…and decreased accuracy in detecting social threat.” She decided that as “the evaluators in the TSST-C remain affectively neutral throughout the task, it is likely difficult for children with autism to detect the component of social-evaluative threat in this experimental protocol.”

The evaluators’ neutrality is designed to pose a social-evaluative threat in that it removes “the element of positive feedback or social support which might preserve the social self” (Olivier Vors, et al., “The Trier Social Stress Test…” PLos One 2018).

Lanni knew the autistic children likely had impaired ability to detect social threat. Why, therefore, did she think it advisable to use the TSST-C on them in the first place? It’s a bit puzzling. However, given that Corbett used the same protocol for stress-testing autistic adolescents in a 2023 study, the choice of protocol was likely Corbett’s and not Lanni’s.

In 2008, Simon Wallace, et al. wrote that “deficits in recognising and producing facial affect partly characterise the social impairments in autism (ICD-10; World Health Organization, 1992) and a substantial body of research has attempted to identify what causes these deficits” (“An investigation of basic facial expression recognition in autism spectrum disorders,” Cognition and Emotion).

Of note is that in 2018, E. Loth, et al. found that “the majority of people with ASD [Autism Spectrum Disorder] have severe expression recognition deficits” (“Facial expression recognition as a candidate marker for autism spectrum disorder: how frequent and severe are deficits?”, Molecular Autism).

Although Lanni claimed the children had given assent to the study, she also wrote that “core features of the disorder likely interfere with an individual with autism’s ability to understand the question being asked (e.g. impaired verbal comprehension).”

Autism researcher, autistic savant psychologist Dr. Henny Kupferstein has argued that “to date, autism research is sterile of the authentic narrative from autistics themselves, and lacks the autistic’s consent to such exclusion…current autism stereotypes…regard heightened abilities…not as meritorious in isolation, but only as sensational because of a disability.”

Kupferstein proposes an alternative model, “Able Grounded Phenomenology (AGP), a theoretical paradigm shift grounded in the abilities known to correlate with autism…and to bring to the forefront the innate aptitude of individuals viewed through this lens.” By contrast, Corbett and Lanni’s research focuses exclusively on the pathology paradigm.

In 2016, Lanni’s mentor Blythe Corbett wrote, “for many children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), social interactions can be stressful. Previous research shows that youth with ASD exhibit greater physiological stress response during peer interaction, compared to typically developing (TD) peers.”

It is concerning that not only did Lanni, et al. deliberately subject autistic children to simulated social stress, two additional verbal tests were added to the 2011 study. Lanni demonstrates that she knew “children with autism [might] find this task [of verbal fluency] particularly stressful given that they often demonstrate impaired verbal ability relative to typically developing children on tests of verbal fluency.”

While the research subjects used in the Lanni study were assumed to have low verbal skills based on their having autism, and tested for their stress reactions to verbal performance tests, very little research has historically been done on how to improve speech among low-verbal autistic children.

Autism researcher Markus A. Banks writes that “only 31 studies published from 1960 to 2018 looked at methods to improve speech in minimally verbal children with autism. The methods used to measure skills varied from one study to the next: Some used parent reports, whereas others relied on a range of behavioral and language assessments. Definitions of ‘minimally verbal’ also varied widely, with one study specifying fewer than 20 intelligible words and another fewer than 5 spontaneous words per day.”

Lanni’s 2011 dissertation cites a 1987 study by UCLA psychologist Dr. Ivar Lovaas, “Behavioral treatment and normal educational and intellectual functioning in young autistic children.” According to Ruth Padawar in the New York Times Magazine, Lovaas “provided 19 autistic preschoolers with more than 40 hours a week of one-on-one A.B.A. (Applied Behavior Analysis), using its highly structured regimen of prompts, rewards and punishments to reinforce certain behaviors and ‘extinguish’ others. (An equal number of children, a control group, received 10 or fewer hours a week of A.B.A.)”

Padawar continued: “Lovaas claimed that nearly half the children receiving the more frequent treatment recovered; none in the control group did. His study was greeted with skepticism because of several methodological problems, including his low threshold for recovery — completing first grade in a ‘normal’ classroom and displaying at least an average I.Q. (“The Kids Who Beat Autism,” 2014).

Dr. Lanni’s career trajectory 2012-2023

Dr. Lanni obtained her clinical licensure in 2013. Subsequent to 2012, she has not been involved in autism research, evaluation or treatment of individuals with ASD. In October 2016, Lanni co-authored “A pilot study to evaluate multi-dimensional effects of dance for people with Parkinson's disease.” Past 2016, no research publications are listed for her.

Lanni assumed her duties as a neuropsychologist at Kaiser Permanente in 2017, after which her citations took a steep dive. A peak of citations of her work occurred in 2021, then declined dramatically, for a total of 210 overall.

Graph depicting citations of Dr. Kimberly Lanni’s research 2017-2023

According to a now-broken Google link (“Meet My Team Kaiser Neuropsychology Postdoctoral Residency”), Lanni stated that she was “invested in bringing the scientist-practitioner model to life” at Kaiser.

The Clinical Psychology Program at Washington State University, where Lanni obtained her PhD, is based on the scientist-practitioner model of training. According to JC O'gorman in 2001, “The scientist-practitioner model…aims to integrate science and practice to provide a uniquely qualified professional to work in a range of health, human service, organisational, and educational settings. The model…has been criticised on [several] ground(s) [among which are that] professionals trained in programs applying the model do not perform as scientists, as indicated by their low publication rates” (“The Scientist-Practitioner Model and Its Critics,” Taylor & Francis online).

Notably, despite Lanni’s avowed interest in bringing the clinical psychology scientist-practitioner model alive as the team lead of the Neuropsychology Postdoctoral Residency Program, she has never worked at Kaiser as a clinical psychologist per se, nor has she ever been involved in their Department of Research.

Lanni’s work followed in the footsteps of her mentor, Vanderbilt University psychiatrist Blythe Corbett. Corbett also approvingly cited the controversial work of Dr. Ivar Lovaas.

In 2003, Lanni’s mentor Blythe Corbett wrote “Video modeling: A window into the world of autism” (The Behavior Analyst Today.) In the article, she defined autism according to a deficit model: “Autism is a severe neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by qualitative impairment before the age of three in verbal and nonverbal communication, reciprocal social interaction, and a markedly restricted repertoire of activities and interests (American Psychiatric Association, 1994).”

Corbett approvingly cited the controversial work of UCLA autism researcher Ivar Lovaas, known as the father of Applied Behavior Analysis, stating “there is substantial evidence that children with autism show benefit from early-intervention behavioral techniques.”

In a 2005 iteration of the “Video Modeling” article, Corbett cites Lovaas et al.’s 1979 study “Stimulus overselectivity in autism: a review of research” (Psychological Bulletin). The review describes infantile autism as a “severe form of psychopathology in children…characterized by extreme social and emotional detachment…when one considers the behavioral impoverishment of these children, it is understandable that autism is also characterized by a poor prognosis.”

In 2007, Corbett again approvingly cites Lovaas’ 1987 work on autism, stating: “Considerable empirical evidence has shown that early intervention based on applied behavior analysis (ABA) can result in significant, comprehensive and lasting improvements in children with autism” (“Brief Report: The Effects of Tomatis Sound Therapy on Language in Children with Autism,” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders). In the 1987 Lovaas study referenced by Lanni and Corbett, he characterizes autism as “a serious psychological disorder with onset in early childhood.”

In An Open Letter to the NYT: Acknowledge the Controversy Surrounding ABA (2020), Faye Fahrenheit writes: “Within the autistic community, ABA is seen as one of the largest, if not the largest, controversies. It has a dark and deeply unethical past, as well as a highly ethically-questionable present and future.”

In 2018, a study by Dr. Henny Kupferstein found a correspondence between ABA and trauma (PTSD/PTSS) in autistic respondents who had undergone the treatment: “Autistic respondents exposed to ABA were 1.86 times more likely to meet the PTSD diagnostic criteria. Overall, individuals exposed to ABA had a 46 percent likelihood of indicating PTSS. In contrast, 72 percent of non-exposed individuals did not report PTSS. Symptom severity was more harshly graded by respondents concerning ABA exposure” "(“Evidence of increased PTSD symptoms in autistics exposed to applied behavior analysis,” Advances in Autism).

In 2020, D.A. Wilkenfeld and Alison M. McCarthy wrote that “a dominant form of Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA), which is widely taken to be far-and-away the best "treatment" for ASD, manifests systematic violations of the fundamental tenets of bioethics. Moreover, the supposed benefits of the treatment not only fail to mitigate these violations, but often exacerbate them” (“Ethical Concerns for Applied Behavior Analysis for Autism Spectrum ‘Disorder’, Kennedy Institute Ethics Journal).

Ivar Lovaas used electric shock, full-body restraint, severe physical beating and even murder threats to train ‘abnormal’ behavior out of autistic children. Lovaas said autistic individuals were “not people in the psychological sense.”

Dr. Ivar Lovaas using shock therapy on an autistic girl, 1965 (TIME-LIFE Pictures)

Ole Ivar Løvaas (1927-2010) was a Norwegian-American clinical psychologist and professor at the University of California, Los Angeles. Lovaas is considered the father of Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA). Applied Behavior Analysis seeks to improve social skills, using interventions based on principles of learning theory. ABA derives from the work of psychologist B.F. Skinner. In 2014, George Dvorsky wrote in Gizmodo.com that Skinner believed ‘thoughts, emotions, and actions,’ are exclusively products of the environment,” and that he considered free will an illusion.” Mostly experimenting on animals, Skinner showed that behavior can be altered with repeated drills, rewards to reinforce wanted behavior and punishments to extinguish unwanted behavior—the proverbial carrot and stick.

Lovaas took Skinner’s behavioralist premises to their logical extreme. According to Cassandra Kislenkow in Xtra magazine, Lovaas’ used “electric shock, full-body restraint and severe physical beating” in his attempts to train children out of autistic behavior, and “once bragged about threatening an autistic child with murder, writing, ‘I let her know there was no question in my mind that I was going to kill her if she hit herself once more, and … we had the problem licked.’” Following intense criticism, Lovaas eliminated these aversive treatments in the 90s.

In a 1974 interview with Psychology Today, Lovaas notoriously denied the humanity of autistic children: “You see, you start pretty much from scratch when you work with an autistic child. You have a person in the physical sense — they have hair, a nose, and a mouth — but they are not people in the psychological sense. One way to look at the job of helping autistic kids is to see it as a matter of constructing a person. You have the raw materials, but you have to build the person.”

As stated by Lyric Holmans (Neurodivergent Rebel), in 1975, the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) rescinded Lovaas’ funding due to complaints of excessive corporal punishment.

Archeology of a bad idea: Ivar Lovaas and the UCLA Young Autism Project; a 2020 podcast details abusive practices and methodological mayhem behind 1987 Lovaas study

A 2020 podcast featuring Justin Barrett Leaf, Ron Leaf and Joseph Cihon sheds considerable light on the research fraud and abuses that occurred at the UCLA Young Autism Project. Ron Leaf, who worked directly with Lovaas, admitted that the “40 hours a week” of Applied Behavior Analysis was fabricated, as the researchers never actually tracked the number of hours. They settled on 40 because Lovaas said “it felt like a full-time job.” Ron Leaf also admitted that he hit kids hard for stimming, and only stopped because it wasn’t “PC anymore” (thanks to Jeff Newman on Facebook for the documentation). It is jaw-dropping that the “40 hours a week” criteria for ABA, since considered a gold standard for the therapy, came about as the result of fudged data.

In 2019, the 40-hour goal was “formalized by the Behavior Analyst Certification Board, which recommended 30 to 40 hours of treatment per week for autistic children who need help in several areas, such as cognition, communication or social functioning” (Connie Kasari).

The fact that Lanni, Corbett and thousands of others have continued to cite Lovaas’ 1987 dumpster fire inside a train wreck of a study, involving methodology that even the researchers involved admitted was guesswork, and treatment that Lovaas himself repudiated in the 90s, shows the intractability of a bad idea. Tellingly, the same Lovaas acolytes and podcasters referenced above, Justin Barrett Leaf, et al., also criticized Kupferstein’s analysis of the traumatic results of ABA, saying that her study should be taken with “extreme caution” due to “severe methodological and conceptual flaws.” This is a Vantablack-pigmented pot talking trash about an off-white kettle. The methodological and conceptual flaws of Lovaas 1987 Young Autism Project—that you can literally beat the autism out of autistic children, given the will and the time—should be obvious to all with an ounce of humanity.

Applied Behavior Analysis and the evidence problem

According to Rachel Zamzow, evidence that ABA actually works is slim: “A 2020 study — the Autism Intervention Meta-Analysis, or Project AIM for short — plus a string of reviews over the past decade also highlight the lack of evidence for most forms of autism therapy. Yet clinical guidelines and funding organizations have continued to emphasize the efficacy of practices such as applied behavior analysis (ABA). And early intervention remains a near-universal recommendation for autistic children at diagnosis” (“Why Autism Therapies Have an Evidence Problem," Autism Research News).

Corbett 2006-2008: Study of children who “suffered from autism” involved “mild restraint” and “unpleasant noises”; 21 autistic boys and one girl were generalized to all “children with ASD.”

Between 2006 and 2008, Blythe Corbett conducted stress studies on autistic children. These studies involved a simulated MRI housed at the UC Davis Imaging Research Center (IRC). In 2008, Corbett wrote “the mock MRI was used as a moderate stressor that involves mild restraint, novelty and exposure to the computer-simulated unpleasant noises generated by the MRI scanner” (According to GEhealthcare.com, “studies show that at their loudest, an MRI scanner generates about 110 decibels of noise, which is about the same volume as a rock concert”). The research subjects were 44 children between 6 and 12, 22 neurotypical and 22 with a confirmed diagnosis of autism. The autistic subjects (in Corbett’s words, those who “suffered from autism”) were primarily boys, with only one girl, while the neurotypical cohort contained three girls. Their ethnic background and other demographic information is unknown.

The purpose of the studies “was to investigate the neuroendocrine activity of children with high-functioning autism in comparison with typically developing children,” Corbett wrote. “The primary aims [of the study included] …response to stress…in children with autism of an enhanced cortisol response to first exposure to the mock MRI; response to a repeat exposure to the mock MRI; and…response to the real MRI environment.”

Corbett wrote that “just over one-half of the participants (n = 28) in the [2008] study returned to the IRC for a second visit (Mock 2) and a real MRI scan. For various reasons (e.g., time constraints, not wanting their child exposed to a real MRI), some families chose not to complete this portion of the study.”

Corbett observed that “though the children with autism did not consistently demonstrate an initial cortisol increase following exposure to the initial stressor, they showed an elevated cortisol response at the arrival for the second visit to the mock MRI.”

Mock MRI Scanner, Children’s Hospital of Pennsylvania

Auditory Hypersensitivity/Hyperacusis in Autism Spectrum Disorder

In 2008, Erissandra Gomes, et al. published the study “Auditory Hypersensitivity in the Autistic Spectrum Disorder.” Gomes concluded that “sensory-perceptual abnormalities are present in approximately 90% of individuals with autism,” and that auditory hypersensitivity was present in between 15 and 100% of the autistic population.

Temple Grandin writes: “Autistics must be protected from noises that bother them. Sudden loud noises hurt my ears like a dentist’s drill hitting a nerve. A gifted, autistic man from Portugal wrote, ‘I jumped out of my skin when animals made noises’ (White & White, 1987). An autistic child will cover his ears because certain sounds hurt. It is like an excessive startle reaction. A sudden noise (even a relatively faint one) will often make my heart race. Cerebellar abnormalities may play a role in increased sound sensitivity. Research on rats indicates that the vermus of the cerebellum modulates sensory input (Crispino & Bullock, 1984). Stimulation of the cerebellum with an electrode will make a cat hypersensitive to sound and touch (Chambers, 1947)” (autism.org).

In 2009, Robert Morris wrote, “many individuals diagnosed with autism experience auditory sensitivity, a condition that can cause irritation, pain, and, in some cases, profound fear” (“Managing Sound Sensitivity in Autism Spectrum Disorder: New Technologies for Customized Intervention,” MIT Media Lab).

In 2021, Zachary Williams et al. published a study “Prevalence of Decreased Sound Tolerance (Hyperacusis) in Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Meta-analysis.” They wrote “we found a high prevalence of current and lifetime hyperacusis in individuals with ASD, with a majority of individuals on the autism spectrum experiencing hyperacusis at some point in their lives.” (Notably, Williams is a colleague of Corbett’s at Vanderbilt University.)

David M. Baguely writes, “Hyperacusis has been defined as 'unusual tolerance to ordinary environmental sounds' and, more pejoratively, as 'consistently exaggerated or inappropriate responses to sounds that are neither threatening nor uncomfortably loud to a typical person’” (“Hyperacusis,” Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 2003).

Sensory perception disorders, which include hyperacusis, are listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition, text revision (DSM-5-TR) as a factor for an autism diagnosis.

In 2022, N. Stogiannos, et al., wrote in Radiography, “the narrow bore of the MRI scanners, the acoustic noise from the gradients…in conjunction with the increased rates of anxiety and sensory sensitivities reported among autistic individuals, may pose significant challenges to patients when undergoing MRI examinations” "(“Autism-Friendly MRIs…”).

“Acoustic noise” can interfere with fMRI brain studies

Michael E. Ravicz noted in 2000 that an “undesirable aspect of present-day MRI is the high-level sounds…these unwanted sounds, or ‘acoustic noise,’ pose particular difficulties for functional MRI (fMRI) studies that measure brain activation in response to sound stimuli. For example, the background noise can mask the stimuli…and the noise itself can produce brain activity that is not related to the intended stimuli (“Acoustic noise during functional magnetic resonance imaging” Journal of the Acoustic Society of America).

In light of Ravicz, one wonders why Corbett, et al. apparently did not factor in that the noise emitted by the actual fMRI machine would likely produce additional brain activity that might either wipe out, dilute or amplify the previous effects of the mock MRI.

Why did half of the research participants not return for the second exposure to the mock MRI, and what accounts for their elevated anticipatory cortisol levels?

The fact that half of the research participants in the Corbett study did not return for the second exposure to the mock MRI under conditions of mild restraint, combined with the elevated anticipatory cortisol levels of those who did, and the failure of many who remained to complete the actual fMRI portion of the study, suggests several things:

That due to the likelihood that they have hyperacusis, the autistic children may have associated the mock MRI with discomfort and distress, and did not wish a repeat experience.

That the past experiences of mild restraint and unpleasant noises might have had a traumatic impact on these children.

Autism is characterized by “insistence on sameness, inflexible adherence to routines, or ritualized patterns” (DSM-V). Given that autistic people often rely on predictability and routine to feel safe and secure, the uncertainty surrounding the second visit to the mock MRI machine, in addition to the unknown variable of exposure to an actual MRI machine, may have contributed to anxiety and stress, leading to increased anticipatory cortisol production.

That both autistic and non-autistic children in the very tiny study cohort experienced the anticipation of re-exposure to the mock MRI as distressing. The takeaway there is that very loud sounds and mild restraint don’t feel good to children, regardless of whether they are neurotypical or neurodivergent.

In a version of Lanni’s doctoral dissertation epublished in 2011, she wrote that “children with ASDs vary substantially in their cortisol responses but do not differ as a whole from typically developing children in their response to acute nonsocial stress (mock-MRI; Corbett et al., 2008)…anticipation of repeated exposure to nonsocial stress (mock-MRI; Corbett et al., 2008), or physical stress (exercise; Jansen et al., 2003).”

Neither Corbett nor Lanni seem to have taken into account the fact that fully half of the participants did not return for a second go-round of “acute” nonsocial stress. This fact, combined with the extremely small sample size of the test participants, undoubtedly skewed the testing results. Moreover, the 99% boys between 6-12 that participated in Corbett’s studies cannot be taken as universally representative of “children with ASDs.” It is also telling that Lanni characterized the stress of the mock MRI as “acute.” Use of the term indicates that the stress experienced by the autistic children in response to the sounds was significant and intense but time-bound, and that the stress response is psychological rather than physical (eg, heightened cortisol levels).

Other methodological flaws of the study include lack of a control group. The study compared children with autism to neurotypical children, but it did not include a control group or groups that experienced neither unpleasant noises nor mild restraint. This omission makes it difficult to determine whether the observed anticipatory stress reaction is specific to autism or simply a response to the unpleasant stimuli.

Additionally, the fact that half of the participants did not return for a second session with the MRI simulator raises concerns about potential selection bias. It is possible that those who chose not to return might have had different stress responses compared to those who did return.

Curiously, Corbett et al. did not seem to have considered the likelihood that a combination of mild restraint and exposure to unpleasant noises from a simulated MRI machine might induce an anticipatory stress response, given the prevalence of hyperacusis and similar sensory disorders in the autistic population. The other possibility is that Corbett knew exactly what she was doing and deliberately subjected the autistic children to a stimuli she knew would be especially traumatic for them. At any rate, the protocol she chose seems both gratuitous and abusive with these subjects, and produced no useful or generalizable results.

David Amaral: Children with autism not ‘doomed to it at birth”; Corbett speculated about “full-blown prevention” of autism (2005)

In May 2005, David Amaral, then research director at the UC Davis M.I.N.D. Institute, spoke with WebMD about the benefits of detecting autism early through blood testing at birth. Amaral characterizing having autism at birth as “being doomed” to the condition. If scientists could identify the environmental trigger thought to cause autism, this “might allow full-blown prevention, and in other cases more tailored treatment," added Blythe Corbett.

Other controversial research on autistic children

According to NBC News in 2008, the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) “dropped plans to test a controversial treatment for autism that critics had called an unethical experiment on children. [NIMH] said in a statement…that the study of chelation has been discontinued…the agency decided the money would be better used testing other potential therapies for autism and related disorders. The study had been on hold because of safety concerns.”

British doctor Andrew Wakefield ignited a storm of controversy when, according to The Guardian (2010) it was found he had “used children who were showing signs of autism as guinea pigs, subjecting them to invasive and unpleasant procedures including lumbar punctures and colonoscopies that they did not need.”

Wakefield was struck off the medical register for a debunked 1998 study, published as a paper in The Lancet, claiming a link between the measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine and autism. According to Owen Dyer in BMJ (The British Medical Journal) in 2008, “Dr Wakefield’s comments at a press conference announcing the paper…led to a public health scare that saw uptake of the vaccine dip below 80%.”

Dyer stated that “The Lancet later repudiated the paper, after it emerged that Dr Wakefield had extensive financial ties to lawyers and families who were pursuing the manufacturers of the vaccine in the courts and that most of his research participants were litigants.”

In 1999, Dr. Wakefield presented his research to parents of autistic children at the UC Davis M.I.N.D. Institute. During the presentation he told a story about children vomiting after a blood draw at his son’s birthday party, which he later admitted was a fabrication.

Hans Asperger

Dr. Hans Asperger. Credit: Alamy Stock Photo

Among the most heinous practitioners of unethical experimentation with autistic children was Hans Asperger, the Viennese physician after whom a form of high-functioning autism was named. According to Herwig Czech in Molecular Autism magazine (2018), Asperger “managed to accommodate himself to the Nazi regime and was rewarded for his affirmations of loyalty with career opportunities. He joined several organizations affiliated with the NSDAP (although not the Nazi party itself), publicly legitimized race hygiene policies including forced sterilizations and, on several occasions, actively cooperated with the child ‘euthanasia’ program.”

The CIA

The CIA sponsored Dr. Lauretta Bender’s sadistic experiments on autistic children as part of mind-control experiments during the Cold War. According to user AsPartofMe in Wrong Planet (February 2018), “In a published report on her 196 LSD experiments with 14 ‘autistic schizophrenic’ children, Bender states she initially gave each of the children 25 mcg. of LSD ‘intramuscularly while under continuous observation.’ She writes: ‘The two oldest boys, over ten years, near or in early puberty, reacted with disturbed anxious behavior.’”

AsPartofMe’s blog further stated that “Dr. Bender's LSD experiments continued into the late 1960s and, during that time, continued to include multiple experiments on children with UML-401, a little known LSD-type drug provided to her by the Sandoz Company, as well as UML-491…Bender's reports on her LSD experiments give no indication of whether the parents or legal guardians of the subject children were aware of, or consented to, the experiments.”

John Elder Robison: “What’s the point?”

Bestselling author and William and Mary neurodiversity scholar John Elder Robison has close ties to the U.C. Davis M.I.N.D. Institute and is lauded by Corbett’s colleague David Amaral, with whom she has collaborated. Via Facebook messenger, Robison questioned my critique of the work of Lanni and Corbett. “What’s the point?” Robison asked. “The way researchers behave now is the conversation to be having, not what they did a generation ago.”

Robison wrote, “If you have concerns about UC Davis, separate from the study, I suggest you write Dr Peter Mundy, whom I believe is already sympathetic to your concerns. You might also speak to Dr Marjorie Solomon, who is running studies now with autistic input.” He suggested that “it would be far more valuable to look constructively at the practices employed by institutional review boards at major research sites today, and consider how those may be improved.”

I responded that, as I stated in the blog (see “Corbett today”) Corbett has continued to use the TSST-C in her studies up to July 2023, which means that the ethical standards and practices of “a generation ago” (assuming that a decade is a generation) persist to the present day, at least as far as her research is concerned. Robison rejoined: “in my opinion, looking at practices of the past in papers being written today will create the impression that those are today’s practices, and might therefore bias people unfairly against research when in fact the practices have evolved.”

Robison then made a blanket claim that he has “no knowledge of what they [Corbett] do or don’t do, so have no opinion on that.”

I reiterated what I had written in this blog about Corbett’s current research, and wrote that the fact Corbett continues to use the 2011 TSST-C protocols in 2023 creates the impression that these are today’s practices because these are, in literal fact, today’s practices. I then gave him a link to Corbett’s faculty page at Vanderbilt University. “Ok,” Robison responded ambiguously. (I’ve shortened our exchange for the purpose of this blog—I repeated my claims about Corbett at least four times, besides the fact that the blog has her work as its centerpiece.)

I find Robison’s responses both disingenuous and revealing of a conflict of interest. Even supposing Robison had completely forgotten the subject of our Facebook exchange by the close of that exchange, given Robison’s close connections with UC Davis M.I.N.D. Institute and Corbett collaborator David Amaral, it’s unlikely he would have had “no knowledge” of Corbett and her research. Robison also appears on a list of “Past Autism Speakers in Kern County” with Corbett. He serves on the US Department of Health and Human Services Interagency Autism Coordinating CommitteeEditSignEditSign with Dr. Julie Lounds Taylor, who is a colleague of Corbett’s at Vanderbilt University as well as a collaborator with her. In addition, Dr Marjorie Solomon, whom Robison suggested I speak with, is a colleague of and collaborator with Corbett.

Despite the objections of those who, like Robison, believe today’s standards have supplanted yesterday’s abhorrent practices, ethical concerns surrounding research on autistic children still prevail. To take but one example, a 2020 Yale University study on autistic infants was widely criticized for its methods of eliciting fear in the children.

In the study, titled “Attend Less, Fear More: Elevated Distress to Social Threat in Toddlers with Autism Spectrum Disorder,” researchers Katarzyna Chawarska, Suzanne Macari and Angelina Vernetti “terrified…toddlers with things like spiders, dinosaurs with light up red eyes, and grotesque masks. The toddlers were exposed to these ‘threatening stimuli’ for 30 seconds and then given 30-75 seconds to process” (Colleen Berry).

Judge Rotenberg Center 1971-Present

Drawing by a former patient at Judge Rotenberg Center depicting use of the graduated electronic decelerator

According to Lydia X. Z. Brown, The Judge Rotenberg Center (JRC) in Canton, Massachusetts “is an institution for people with disabilities…which includes autistic people, and people with psychosocial disabilities (commonly called mental illness). JRC first opened as the Behavior Research Institute in 1971. Today, JRC is most notorious for their use of aversive contingent electric shock and the device they invented and manufacture in-house, the graduated electronic decelerator (GED).”

Brown describes practices at JRC that appear to perpetuate the worst excesses of Dr. Lovaas, and more: “in addition to contingent electric shock, BRI/JRC has also used extremely prolonged restraint, food deprivation, deep muscle pinching, forced inhalation of ammonia, and sensory assault techniques for behavioral modification.”

In 2013, United Nations special rapporteur Juan Mendez use of the graduated electronic decelerator as “torture.”

The Massachussets Supreme Court ruled in September 2023 that the Judge Rotenberg center would be allowed to remain open, though it left the door open to future challenges (Reuters).

Yale University Emotional Distress study; Corbett today

Blythe Corbett’s research on stress and autistic children continues to the present. In 2020, Corbett published a study in the journal Psychoneuroendocrinology titled “Developmental effects in physiological stress in early adolescents with and without autism spectrum disorder.” The study employed the same Tier Social Stress Test for Children previously employed in Corbett’s work with Lanni. Corbett described the TSST-C as “a 20-min task divided into four subcomponents: 1) Intro/Preparation, 2) Present Speech, 3) Serial Subtraction, and 4) Debriefing.” Notably, Corbett maintained the protocol used in the Lanni study, “ a scenario in which the participant must deliver the ending to a short story in front of a panel of judge…showing neutral facial expressions.”

In 2021, Selima Jelili, et al. found “significant impairments in the FER [Facial Emotion Recognition] performances of…children with ASD…in the identification of anger, disgust, surprise, sadness, and neutral expressions” (“Impaired Recognition of Static and Dynamic Facial Emotions in Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder Using Stimuli of Varying Intensities, Different Genders, and Age Ranges Faces,” Frontiers in Psychology).

Corbett’s most recent work on cortisol arousal in autistic adolescents, “The developmental trajectory of diurnal cortisol in autistic and neurotypical youth,” cites her stress test studies, including those that involved mild restraint and unpleasant noises from a mock MRI machine. The study appeared as an online publication from Cambridge University Press on July 12, 2023.

The UC Davis M.I.N.D. Institute, through which Corbett, et al., conducted their autism research, retains close affiliations with the widely castigated Autism Speaks organization. Unsurprisingly, Corbett’s research has itself been funded through Autism Speaks.

Autism Speaks promotes Applied Behavior Analysis, the controversial behavioralism-based autism treatment approved by Blythe Corbett, among whose pioneers was Dr. Ivar Lovaas.

Christopher Whelan wrote in 2020: “Autism research has rarely if ever meant sociological research into how autistic people fit ourselves into our communities, anthropological research into how we meet our basic needs, or social work research into how most effectively to support autistic people in our goals towards self-actualization. Autism research has normally taken place in test tubes and flasks, and rarely in qualitative interviews with autistic people” (“Shut Down Unethical Autism Reseach”).

Some preliminary conclusions and an answer to Robison

Earlier in this blog, John Elder Robison raised a question: “what’s the point?” he asked, of sifting through this old research for flaws, when bold new approaches and perspectives beckon?

Robison’s critique might have more punch were he not so utterly compromised by his one multiple one degrees of separation from Blythe Corbett and her researchers and his unconvincing protest that he doesn’t know what they do or don’t do. The possibility that he’s had close social and professional interactions with Corbett is non-zero. But even if he had, who cares? I doubt his conflict of interest is unique in the field of autism research, or any field for that matter. In which case, why not simply admit he knows her work? Why not stand up for it? But he hasn’t, and he won’t, for reasons known only to him. (I suspect because it’s bad work, but that’s me). Nevertheless, I’ll make an effort to answer his question.

I’ve been upfront about the fact that I am not a scientist, and moreover have a conflict of interest of my own, my not-so-happy interactions with Dr. Kimberly Lanni, without which this blog wouldn’t have a reason for being. What I’ve discovered in my travels down this particular rabbit hole is that Dr. Lanni is at best a very minor player, whose function seems to have largely been to document, report on and rationalize Blythe Corbett’s studies, rather than originate her own work as a “scientist-practitioner.” It’s telling that she only ever published six articles, with the preponderance of the work being done by other people, after which her career as a scientist dribbled off to nothing while still in her mid-30s. I get the impression that her PhD dissertation was a deal struck with Corbett—Corbett got her NIH grants from it, and Lanni got her doctorate, which allowed her to do the postdoctoral work to get her clinical licensure. Three years later, the publications stopped.

As for Lanni’s own involvement in the seminal salivary studies of 2011, I see her more as a carrier of spit samples, a lab rat, who has leveraged a brief toe-dipping into the waters of real science into a career of cosplay, in which she’s been proud to parade about in a lab coat while hustling her neuropsychology residents through their paces. Which is how my timeline and hers intersected, much for the worse on my side.

With allowance for my crude and uninformed lay understanding of scientific method and statistics, Corbett strikes me as a curiosity. Her entire life’s work seems to revolve around a vital evolutionary adaptation—the HPA axis—without which humanity would not have survived. There’s no doubt in anybody’s mind at this point that stressful conditions activate the HPA axis, causing us to squirt cortisol one step ahead of the saber-toothed tiger. That stressful conditions cause stress has never been controversial. What Corbett wants to know, if I’m understanding things correctly, is how stressful conditions stress autistic people, specifically young autistic people.

Corbett’s ongoing obsession, which she’s passed on to a series of apt pupils, is the measurement of cortisol levels in young autists whom she’s subjected to various sorts of stressors, including those seemingly designed to cause them trauma (I don’t see a lot, or any evidence, that she’s attempted to mitigate any potential harm her research might have caused). The reader may well say, well surely, that is the point—she wants to know how autistic people react to stress, and whether it’s different from that of neurotypicals—which is fair. But then what? What has she done with this information? Has it informed methods and technologies that will help autists accommodate themselves to a world that is frustrating and bewildering to negotiate?

More questions arise then. Specifically, to what extent does Corbett’s research fall on a continuum from Lovaas? At the very least Lovaas had a rationale, however barbaric, for restraining, prodding, poking and beating his autistic subjects—to extinguish behaviors, such as stimming, that he felt represented some form of extreme mental illness, and to eliminate the autistic presentation from the autistic person.

As far as Corbett is concerned, she’s subjected autistic children to restraint and the noises from a mock MRI machine, which a good many people, neurotypicals included, find distressing. I’ve had multiple MRIs, and find the experience terrifying even with sedation—it’s like being buried alive. And why? To test their spit. To see if they’ve got elevated cortisol from increased stress. Common sense would dictate yeah, Blythe, it probably caused them stress. It caused them so much stress, neurotypical and neurodivergent alike, that half of her test subjects didn’t bother to show up for a second round, and of that straggling remainder, most had anticipatory stress, and a good percentage of those didn’t stick around to complete the session with the real fMRI. But rather than concede that the studies simply didn’t work, she published them, and she and her acolytes continue to cite them more than a decade later. The reason? To be brutally honest, it’s probably the money. I haven’t toted up the numbers for the 2006-2008 studies, but the federal grants she obtained for the studies she did with Lanni tally to 2.5 million dollars. Which raises more questions, such as: Have autistic people benefitted in the slightest, and, was that ever even the real intent?

The new blood and a way forward

In 2019, Jacquiline den Houting wrote: “Strengths-based approaches to intervention and support are increasingly accepted as best practice, and treatment goals are increasingly focused on issues of key concern for the autistic community, as opposed to the normalisation of autistic people. (“Neurodiversity: An Insider’s Perspective,” Autism).

Other autistic researchers, such as Dr. Henny Kupferstein with her Able Grounded Phenomenology model, have challenged the pathology paradigm that still prevails in the field. It is hoped that the infusion of new, neurodivergent blood into autism studies will shift the focus of research from work like Corbett’s, which still emphasizes the deficits of autism, towards a powerful affirmation of the strengths and capabilities as well as the complex needs of all those who inhabit the spectrum.

A Response from Dr. David Putrino

Mount Sinai, New York neuroscientist David Putrino responded to this blog: “I'll confess that I'm not an ASD researcher, so I don't have deep knowledge of the research landscape. I can comment in my capacity as the Director of the Charles Lazarus Children's Abilities Center, where we provide outpatient rehabilitation services for children with various ASD diagnoses and work on accelerating the path of novel technologies that may enhance the quality and efficacy of services that we provide. To this end, we have a very simple and direct strategy and position that we employ when providing services and supporting innovative technology in this population:

Neurodiverse children have a fundamental right to receive interventions that focus on them accessing appropriate accommodations for their neurodiversity, or easing the overall symptom burden that comes from navigating environments designed for a neurotypical population. We do not endorse or employ technologies that attempt to "train" neurotypical behaviors in neurodiverse people. We view that as tantamount to training neurodiverse people to experience daily pain and discomfort in order to navigate a neurotypical world, rather than creating/advocating for accommodations that enable them to thrive in these environments.”

###

NOTE: I am soliciting the feedback, participation of and collaboration with any and all interested members of the autistic community in evaluating the merits, or lack thereof, of the above-mentioned research studies. I am neurodivergent but not autistic. I can be reached through my email which is georgebailey679@gmail.com.

###